Perhaps the last thing you might want to watch right now amid a global pandemic that has totally upended our lives would be a film about a not-so-distant future Armageddon. When we imagine the end of the world, what typically comes to mind are images of freak events that happen in a flash, resulting in the almost total annihilation of mankind in a matter of weeks followed by a desperate remaining few who fight it out among themselves for a cut of the dwindling resources. What sets Children of Men apart from other end of the world fictions is its pace of decline, and the way it explores the death of humanity not with a bang, but with a whimper.

It depicts a failing world – not totally unalike to our own – where an unexplained infertility crisis has struck, and where no woman has given birth in 18 years. We follow the story through the lens of Theo, a civil servant and former activist disaffected with and cynical about the world around him. The film begins in a coffee shop, where people have congregated around the telly as news reaches them that Baby Diego, the world’s youngest person, has been stabbed to death. Theo, disinterested, picks up his coffee, pays, and exits on to the grimy street. As the camera homes in on him pouring whisky into his cup a bomb rattles through the scene, blasting violently in the background as alarms blare and a woman emerges from the carnage, horrified and carrying her severed arm.

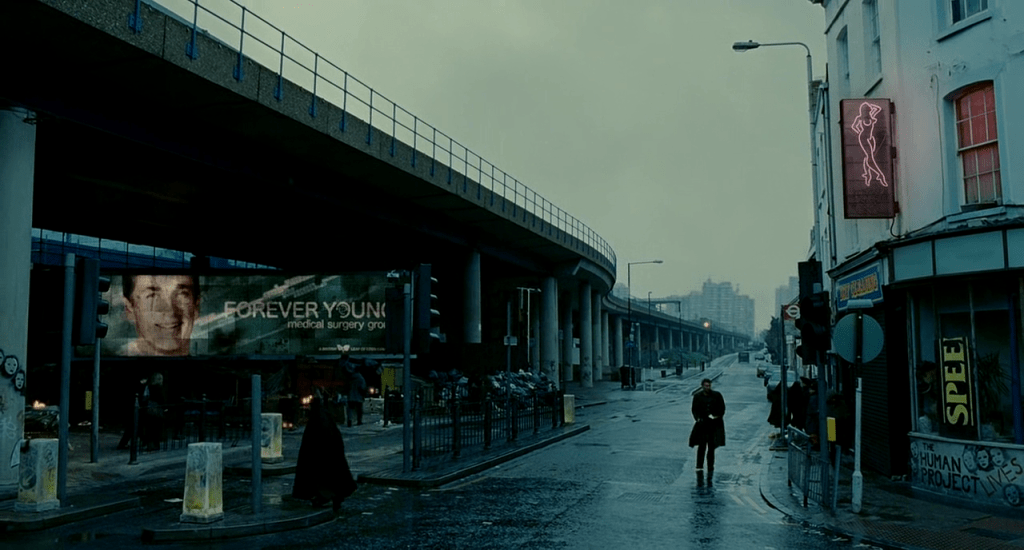

The opening scene really sets the tone for the rest of the film in that it’s a fine exhibit of director Alfonso Cuarón’s grasp of immersive filmmaking. Cuarón manages to craft a richly detailed, depressing world through exquisite attention to scene composition and extensive, meandering shots that take their time to reveal to the viewer what he wants you to see. Everything from the costuming to the adverts on the side of passing buses feels considered and purposeful. I’ve watched this film a dozen times and still I notice new things lurking in the background. If good writing is where the audience is placed in the role of detective then this film is surely a masterclass in storytelling, where showing rather than telling is the preferred method of developing its many themes.

Having grabbed the audience by the horns the story commences, and the tension rarely ceases to dominate for the remainder of the film. Through media clues and other background snippets we find that the rest of the world has utterly collapsed, and that it is only Britain that soldiers on despite it all. Still, the situation seems less than stable. A harsh immigration scheme rounds up and detains all illegal immigrants (referred to derogatorily as ‘fugees), whilst a militant organisation known as the Fishes are engaged in an insurgency against the government in the name of immigrant rights.

Walking through London after the attack Theo is kidnapped by the Fishes, who demand that he secure official transit papers for a young refugee called Kee. Theo discovers that their leader is his ex-wife Julian, and reluctantly agrees. Kee, it transpires, is no ordinary refugee. She happens to be miraculously pregnant, which to the Fishes makes her a useful asset to their cause. Theo is entrusted by Julian to deliver Kee to the Human Project, a secretive and elusive underground group dedicated to researching and solving the fertility crisis, but infighting amongst the Fishes has meant that the police state and other actors are hot on their heels and closing in on them fast.

The film is exhilarating and high stakes, and it serves as both a condemnation and celebration of human nature. Despite the almost religious significance of Kee’s pregnancy, the despair and decline of the human race devoid of youth for nearly 2 decades has ripped society apart seemingly beyond repair. The film means many things to many people but I think principally it’s an exploration of hope. Theo only met Julian because he was once an activist himself as a young man, but this has given way to the realism of adulthood as he settles for a career as a bureaucrat and accepts the inevitable.

This defeatism pervades right across the fictional Britain of 2027; we learn that anti-depressants are handed out in the rations whilst peppered throughout the film are adverts for Quietus which appears to be a euthanasia drug. As Kee and Theo explore an abandoned primary school, one of the Fishes talks about how the sound of the playgrounds fading quickly gave way to despair: “Very odd what happens to a world without children’s voices”. Kee’s child is really a symbol of restored hope for the future, and even the cynical outlooks of Theo and others seem genuinely transformed by the revelation of her pregnancy.

Children of Men is a rare gem of cinema, in that the main plot (remarkable and entertaining as it no doubt is) is almost secondary to the wider world in which it takes place. The film raises a lot of big questions about human nature, childhood, and society. Media narratives are a particular theme of focus and the film is sort of self-referential in the way that it focuses very clearly on a single story when the bigger picture is just as important. It delves into the meaning of context too particularly when Theo goes to visit his government minister cousin who now owns the works of Picasso and Michelangelo, which with nobody to admire or critique them are essentially rendered meaningless.

All around Theo are references that endear you to the complexity of the crisis. At one point there’s a crowd of religious fanatics calling for people to repent near Trafalgar Square. Public service announcements warn against terrorist activity, helping illegal immigrants or skipping mandatory fertility testing. Renegades throw missiles at the caged train carriage that Theo commutes on whilst radio stations indulge in nostalgia for a time before the crisis. On closer analysis there are also references throughout to popular works of art. There’s just such a meticulous attention to detail that makes repeated viewing deeply rewarding; the world shown on screen is so fully realised that it feels like you can just reach out and touch it.

Children of Men has really stood the test of time as a dystopian vision of the future with real relevance to today, especially in the way it touches on migration and our treatment of foreigners. I think it has a lot to say and watching it last month whilst we suffer through another lockdown was a unique experience of its own. On a final thought, I think what’s most fascinating of all about the apocalypse that it envisages is not mass infertility per se, but rather the loss of the future. You don’t need children necessarily – at only 18 years into the crisis there were surely plenty of people around to keep society running – but the simple idea that there’s nobody to inherit the earth is far more damaging than any practical consideration that might come about from the end of human reproduction. At least in the miserable short-term perspective of lockdowns and having nothing to look forward to that’s certainly something we can all relate to.

Words by Charlie Forbes

Leave a comment