Humza Yousaf has endured the weekend with several chronic headaches. It’s party conference season, and that means it’s time to rally the troops, shape the narrative, and set out your stall to voters. Sunak and the Tories had a trainwreck conference of their own, as questions over the fate of a high-speed rail line dominated the event and eclipsed the rest of their agenda. Labour was buoyant as it dished out its ‘bombproof’ policies, with the only real mishap of the weekend being Starmer getting clarted in glitter before his keynote speech. Yousaf meanwhile is facing down existential threats, with his brief tenure as leader of the SNP already on the brink.

Part of why Yousaf is in such a pickle is all to do with a satellite town on the outskirts of Glasgow, which took to the polling booths to elect a new MP in a by-election. This by-election in Rutherglen and Hamilton West (called after a successful petition to recall the constituency MP Margaret Ferrier following a bizarre saga involving pandemic rule breaking, police probes and a parliamentary suspension) resulted in the seat changing hands to Labour’s Michael Shanks. Politics is often a zero-sum game, and Labour’s jubilant mood a week ago is inversely linked with what is shaping up to be a dreich conference for the SNP.

And while the SNP party line last week was to play off their crushing loss as a flash in the pan result, one where voters channelled their anger towards a disgraced grifter, events since have rubbed salt on the open wounds. A defection is always humiliating for any party, but for the SNP’s Lisa Cameron to cross the aisle to the Conservatives on Thursday morning must have felt like a betrayal of a different kind. The SNP’s leadership has responded with true to form denialism, suggesting that she probably never believed in Scottish independence anyway.

On the surface this is just one constituency changing hands, and one MP changing party. But in the bigger picture, the events of this month mark an inflection point for the independence movement. The by-election in particular signals the start of what may turn out to be an extensive stint in the wilderness for the SNP, a stint that will be marred by in-fighting, soul-searching, and – possibly – revival.

To see this writing on the wall, it’s important to be clear on the timeline which has preceded the SNP’s defeat in Rutherglen, and for that we should also be reminded of the heights the nationalists have fallen from. Just as Margaret Ferrier was flouting lockdown rules in 2020 while infected with Covid-19, the party she was part of was riding the crest of an almighty wave in the polls. The pandemic had exposed Westminster and Boris Johnson’s government as utterly dysfunctional. By contrast then-First Minister Nicola Sturgeon seemed at a minimum to be a more competent, evidence-driven administrator. And as the rumour mill of Partygate got spinning, support for independence had never been higher.

Yet the SNP in the last 6 months has suffered a dramatic fall from grace following Sturgeon’s resignation. Where not so long ago their dominance in Scottish politics seemed impregnable, on the turn of a dime the winds have changed, and their future doesn’t seem so certain.

Though Sturgeon denies it, the timing of her resignation in February seems especially suspicious given Police Scotland’s shock inquiry into the SNP’s finances. The party stands accused of mis-using funds they raised and had promised to ringfence for a second independence referendum. It is alleged that they have instead dipped into the war chest to finance frivolous day-to-day spending in the party. In a memorable development, the motor home of party chief executive Peter Murrell’s mother was seized in relation to the ongoing investigations. Regardless of the eventual outcome of the inquiry, the image of power couple Sturgeon and Murrell being arrested and taken in for questioning is now emblazoned into the national consciousness.

The fallout from Sturgeon’s departure has triggered an identity crisis for the SNP. Who are they as a party without a charismatic, strong-willed figurehead to lead the way? It could be argued that Salmond and Sturgeon represent two of not just Scotland but the UK’s most effective politicians of their generation, having taken a ragtag, kooky party from the fringes and into government, and coming within a hair’s breadth of dissolving the United Kingdom.

The candidates to replace Nicola stood totally in her shadow. Humza Yousaf was surely the best of a bad bunch, however he lacks the gravitas that was a hallmark of Sturgeon’s steely leadership style. Kate Forbes may well have been her preferred successor, were it not for her backwards social attitudes and daft media judgement that allowed them to be aired in public. Alas, Sturgeon never found someone truly worthy of passing the torch to. Lightning struck twice for the SNP with Salmond and Sturgeon; perhaps expecting a third was never realistic. Without a clear heir, the leadership race to take her place was bruising and full of venom.

Though Sturgeon’s command masked it well, the SNP are as divided a party as any. Lisa Cameron’s stinging defection to the Tories could not be better illustration of this point. The shared dream of Scottish independence can momentarily obscure unbridgeable differences between the people who believe in it. But when that dream collapses and feels increasingly out of reach, the aftermath can be brutal.

Sturgeon ran out of road when it came to options of how to secure an IndyRef2. She knew it, and it’s clear that even more than the impending police investigation she surely must have known was coming, this was the biggest obstacle to her carrying on as First Minister. Yousaf has now been left scolded by the proverbial hot potato: inheriting a PR mess of a police investigation, restless and increasingly emboldened rivals from the SNP’s many wings, and a constitutional checkmate that Sturgeon has deftly skirted responsibility for. You can’t help but feel sorry for him.

Which brings us to the by-election and its outcome. Though just 30,477 people turned up in the rain to cast their votes, the snap poll carries a suggestion of where Scottish politics could be headed over the next decade. It’s worthwhile viewing the by-election not through its result (as it’s hardly a representative sample size) but instead by the results it will have, and especially the implications it has for Humza Yousaf’s tenability as Scotland’s First Minister, even as his time as leader has barely had the chance to get off the ground.

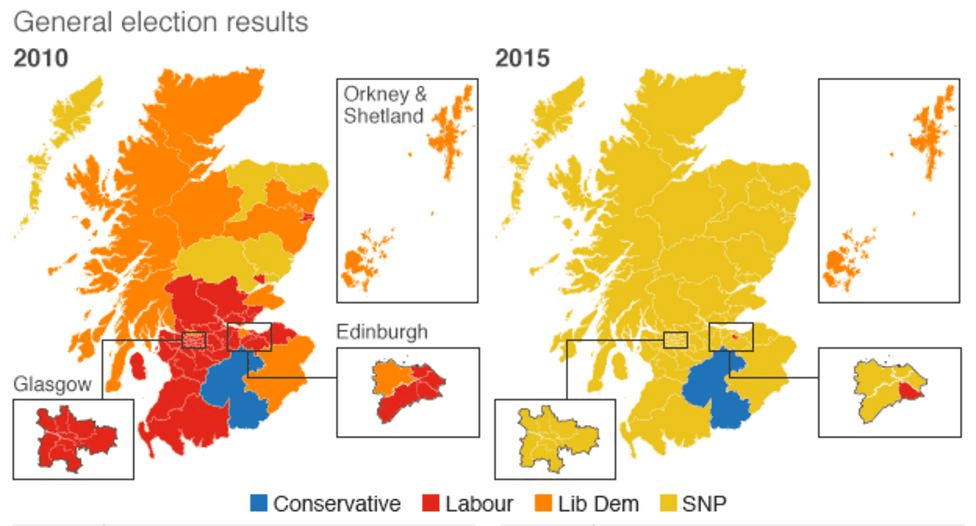

The story of the SNP’s long fall will be written in Labour’s ascendancy. Labour is on the march once more, having suffered its own traumatic spell of irrelevance in Scotland which saw them virtually wiped off the map in 2015, cast adrift to ponder their purpose. Squeezed out by a strident centre-left SNP and staunchly unionist Scottish Conservative party, the party has been a distant third north of the border for some time now.

Once between a rock and a hard place, Labour’s promising polling in both Scotland and England doesn’t so much represent a party popular in its own right, but rather a party no longer being crushed under a ruthless pincer movement. Labour has some precious breathing room as the Tories continue to flounder and the SNP collapses under its own weight.

The truth of the matter is, the SNP and the Tories need each other more than they’d both like to admit. As mentioned, the Tory omnishambles that has raged ever since Brexit has reaped dividends for an SNP desperate to prove to Scots that Westminster is corrupt and uncaring. For the Tories the bogeyman of Scottish nationalism has made for an excellent club to beat Labour with in England, as evidenced by the infamous ‘in Salmond’s pocket’ attack ads against Ed Miliband in 2015.

As mentioned, the high water marks of support for Scottish independence have directly followed political car crashes that have been the fault of the Conservatives in Westminster. Be it David Cameron’s Brexit, Boris Johnson’s blatant lies or the calamity of Liz Truss’s premiership, it could be argued that nobody has made a better case for Scottish independence than the Conservatives themselves. If polls are to be believed and Starmer’s Labour really are on a trajectory to power, ironically one of the biggest threats to the SNP’s dominance in Scotland could be Rishi Sunak being turfed out of Downing Street.

This is not to say that the Labour Party will restore order to the galaxy and reign in perfect harmony, but that on an objective basis the last 13 years of Conservative government have confirmed the worst of Scottish people’s suspicions about London rule: that Westminster is remote, self-serving, conniving, and indifferent to Scotland’s needs. Keir Starmer will have his work cut out to prove to Scots otherwise, however given that Scottish votes lie between him and the keys to Number 10, you can be sure it is in his best interests to do so.

If we had a crystal ball, what might gazing into it reveal about Scotland’s political future many years down the line? Predictions are a fool’s errand in politics, and naturally the vision gets murkier the further away we look, yet there are forces in motion that we can trace forward and offer reasonable estimations about where they will land us.

Prediction one: the Tories are headed for oblivion. This seems obvious, but it’s not guaranteed. But if we take the consensus and the polls at their word, Rishi Sunak will lead the Conservative party to a humiliating defeat next year at a general election. With no star candidate to replace him, and shameless opportunists like Suella Braverman and Kemi Badenoch already sharpening their knives in plain sight, the Tory party – famously Britain’s most successful yet ungovernable party – will eat itself from the inside out, and voters hate parties which hate themselves.

Prediction two: Scotland will finally move on from independence as a defining issue. Hear us out – independence will still matter, and still rouse people’s opinions and stir debate, but increasingly people’s votes will become uncoupled from their strongly held views on whether Scotland should go it alone. Without a second referendum firmly in the calendar, issues such as public services, cost of living, the housing crisis and the climate emergency will once more be front and centre.

Prediction three: the SNP will endure a long fall. Humza will cling on until next year’s election, and depending on the scale of the SNP’s losses probably won’t make it to campaign at the next Scottish parliament elections scheduled for 2026. But whether it’s Humza Yousaf, Kate Forbes, or Bonnie Prince Charlie back from the dead, any leader of the SNP will have to contend with the basic reality that there is no practical, legal route to a second referendum, and more dangerously, fellow SNP members who refuse to accept that this is the case.

We could make a fourth prediction, but it is entirely based on the whims of hope rather than tangible evidence.

To return to the point that the Tories have been the best argument in favour of Scottish independence, is this really a great premise for forming a new country? What progress has actually been made by the broader independence movement since 2014 to iron out the practicalities of what an independent Scotland might look like, or to refine the inclusive emotional message needed to make it over the line? Perhaps a long, painful banishment to the side-lines for the SNP would be the bitter medicine needed to work through these roadblocks. After all, as Labour’s unlikely comeback proves, bad fortune in politics doesn’t last forever.

Words by Charlie Forbes

Cover photo by Scottish Government / Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Leave a comment